In this chapter I am returning home after my first full term at boarding school

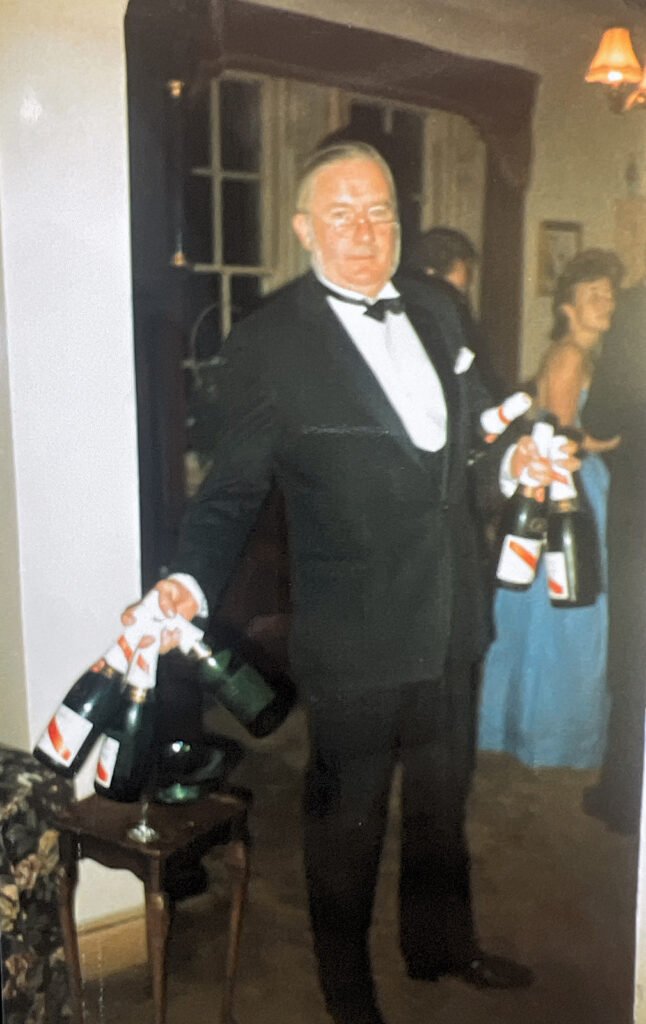

The trouble with scattering your children across the country is that you have to go and fetch them, and what with there being so many exeats, holidays and half terms, socialising for adults can be severely limited unless you make a conscious effort to combine the two. From my classroom, the Christmas holidays of ’72 had seemed like they were never going to arrive, but they did. Father’s diary entry outlined the arrangements: ‘Celia collected Paul & Brian Elliott brought Nicola Home. We had champagne cider for lunch – they didn’t like it! 20 people for Drinks in evening and then up to Woodsome Hall Dance‘. It was useful to know a similarly fragmented family, as the burden of heavy mileage could then be shared. The champagne cider did not feature in my diary entry: ‘END OF TERM. Mr Elliott brings me home – kissed cats – tidied up bedroom from unpacking for it was a mess in my opinion – stayed up late – Helped Mummy with cocktail party – they go out – read comics – glad to be home‘.

Mrs. Moorhouse had already done the bulk of the work to ready the house for guests. As soon as I had shed my school uniform into the laundry basket, I set about the crucial task of exhibiting crystal flutes and skewered sausages on silver platters. Mother and Father were excited about their pre-dance booze-up. I was excited to be home for Christmas, to receive a greater parental allowance than was on offer at half term. I wanted to return to the life I had before. I didn’t like my new one.

In our pyjamas, we watched from the staircase, foreheads resting against the cold balustrade, theatre-goers without tickets to this pantomime. Cars rolled up one by one to drop stockinged legs in high heels at the front door before they glided down the length of the drive and parked up. Glass clinked against champagne bottle; the laughter grew; voices vied to be heard over the general mumble. The reek of cigarettes bled into the curtains.

Adult parties seemed to demonstrate everything Father called out as unseemly behaviour for gentlefolk: flirtatious eyeballs resting on another man’s property, raucous encouragement from wives delighted to show their disinterested husbands they were not without beguiling charm. Lashings of perfume and aftershave dripped off intrigue, undercurrents, lust, revenge on a plate. In this game of charades, the actors had to guess who was double-crossing whom, the double agents amongst them hoping they could seek out the predilections of others while hiding their own. And then everyone was gone, but not the ash-filled carpets, discarded butt-ends, lipstick-stained glass rims. Peace descended. I have returned. They have gone out. After a bout of television, the babysitter retired us to bed, me with a cat under each arm. The fluffboxes seemed pleased to see me – they had been short of someone to carry them about from room to room.

For all the frivolity, Father’s diaries were painting another picture. A tension was mounting as he noted the interest Mother was receiving from other men. They were caught up in their own dramas, so I’m not sure they had detected the change in me. A quietness had descended. The supermarket trip was now all about being by my mummy’s side, holding onto the trolley, taking in her scent and her voice. ‘Nicola, you don’t have to cling to me, you know. I don’t know what’s up with you today. Look at all those biscuits. Choose something you want. Now, off you go‘. Something I wanted; that was an empty offer. It wasn’t on any shelf and wouldn’t be found stuck up with a price tag. Unable to tell her this, smarting at being pushed away, I sallied forth to the biscuit aisle. She was used to having one child, so three at her heels probably seemed like a crowd.

In the mornings, revelling in the ownership of a bed that had no time limit on its occupancy, I could hear her laying the breakfast table, lining up cereal packets for us to pick between Ricicles, Frosted Flakes and Sugar Puffs. What had been normal before was now exceptional. There was no clanging bell to summon me; just the gentle radio in the kitchen playing Kenny Rogers or the Carpenters – Mother had swapped love for love songs.

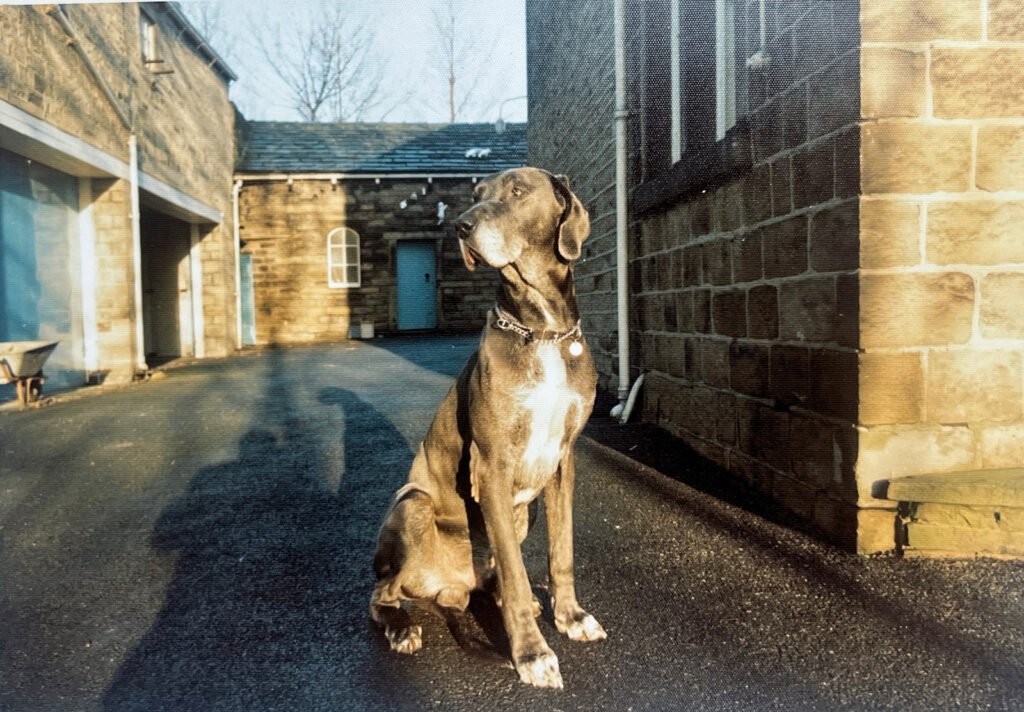

My dolls and teddies had been waiting for me (although Angela had obviously had her fingers all over them); Basil was still happy for me to lie on top of him in front of the coal fire; life seemed almost normal. Apart from the sickness that started on day one, the jelly-wobble malaise of knowing I was there, but soon not. Whereas everything had just been there, always there, now it existed for the sole purpose of teasing me as to how life might be if I were to attend a local school. Four weeks at home sounded good, but the holiday had a predetermined end which every day dragged closer. Time had a purchase price which I would have been only too happy to pay, both to have more and to have less, relative to the start or end of term. At the top of my Christmas list, I should have asked Father Christmas for a Groundhog Day, preferably about 22 December, when the prospect of presents would be electric and the end of the holidays sufficiently distant to be of no immediate threat. That happy day could endlessly repeat as a way of avoiding those long days spent hoping things might be different, even when this was a known impossibility.

Would they have believed me if I had spilled the beans about my isolation at school, about having no friends, about my fear of their next prank? Or would that be like talking to the jailor, any indirect complaint to the housemistress only inviting further torment from my fellow dormitarians?

The grandfather clock, guarding the bottom of the stairs, set the rhythm of the house from its sentry box, plodding out its tick and its tock as it shunted the days along in its sleep; it was in no rush and had nowhere to go. Time was on its side. Time was forever. Standing beneath its busy face, all fussy dials and Roman numerals, I knew it to be a liar. It needed to be told. YOU, you eyeless stately timepiece, are a LIAR. You are as useless to me as our stump of a sundial on a cloudy day from its raised seat amongst the roses. Your poor relation, the wristwatch that follows me everywhere, tells me the truth. It tells me I have only an hour left at home, or an hour to wait before Parents arrive to see me, or an hour before I might get a letter from Mother. Time was everything. At eleven, I was precocious in this knowledge.

Life can be full of contradictions. Having been so unhappy at school for so long, now that my wish had been granted and I was at home, I felt so restless: ‘Did Christmas shopping – very bored – finished music piece which was meant to take all holiday‘. Former pastimes seemed beneath me, but I had nothing to replace them. Summer’s bright blue skies had fled, leaving only a colourless, sinking blanket. The weeks and the weather had moved on. This is all I had thought of, but this new version of family routine was unsettling. If school was a shock, so too was seeing Parents behave as if there was nothing different. Nothing mentioned. Was I imagining it, that I had just been at school for thirteen weeks? Now I didn’t want it to be as before; I wanted a celebration of my return. ‘Home for lunch. We are all very happy to be together again. Very busy at office. Looks as though we shall make lots of money‘. He wrote it, but he never said it– that he felt happy when we were together.

With lunch served, I was in; purposeful, secretive, desperate to get my fair share, it being a certainty there would be nothing to take home. Adults leaned over tables to collect their poached salmon or game terrine without noticing the spoon sinking into the shimmering, extinct white volcano streaked with chocolate butter lava flows. I could not eat another thing from getting home to the babysitter’s arrival as I was feeling a little sick. I liked to be right. There were no leftovers. Somebody ate it all.

The honour of decorating the Christmas tree fell to me this year. Keen to get going, I was in and out of the attic and up and down the stairs with greater enthusiasm than was ever applied to the lacrosse field. All seemed in order. Our crowning golden angel had not been de-robed by mice. The wings of my beloved white goose were ready for yet another season of flapping up and down on its spring, attacking anyone of a certain height who ventured too close to the central light fitting in the inner hall.

I regretted passionately not having the patience to restring those baubles where the threads had broken the year before. The tedious task of making up loops with which to append them to the tree was fiddly, clumsy fingers crushing the funnels on the more fragile glass soldiers and cars, rendering the act of having carefully stored them away pointless. There was plenty of suitable cotton thread round and about, what with the colour of my school uniform being sort of fir green. I knew what to do here, at home, when there was no whispering behind my back, nobody vying to replace me in this activity. It was my role, as of right, to be their daughter and eldest child, a role I filled with ease. My discomfort was in not knowing what that role entailed when I was away, out of sight.

Enjoyed what you read?

Subscribe to Nicola’s newsletter to get first dibs on the full book and behind the scenes content.