It was Jane Austen who said if you gave a girl an education and introduced her properly into the world, ten to one she would have the means of settling well, without further expense to anybody. Jane did not have in mind the promotion of jobs for women, only that they would have a better choice of husband if they could engage in something more interesting than just pretty parlour talk.

My school, Cheltenham Ladies’ College, opened its doors to the daughters and young children of noblemen and gentlemen from around 1856, after the founders of the college felt it was about time an education should be available to girls. The modesty and gentleness of the female character were to be preserved at all costs, for if these young women failed to maintain their suitability as wives, mothers, friends and companions to men, there could be nothing but trouble ahead.

Dorothea Beale, the College’s headmistress, commented in February 1880 on the objections that had originally been thrown in the way of the school’s start-up. The town of Cheltenham was a conservative place, and the very name of the school frightened its inhabitants. Some feared girls would be turned into boys if they attended a college! In her history of the school, Ms Beale wrote:

The kind of education we gave was not approved. Our curriculum was too advanced, though it would now be considered quite behind the age. It embraced only English studies, French, German, and a very little science; all taught, it is true, in a somewhat thorough way … “It is very well,” said one mother, who withdrew her daughter at the end of the quarter, “for my daughter to read Shakespeare, but don’t you think it is more important for her to sit down to the pianoforte and amuse her friends!” … “My dear lady,” said one father, “if my daughters were going to be bankers, it would be very well to teach arithmetic as you do, but really there is no need!”

Fortunately, formidable women like Frances Buss and Dorothea Beale advanced the cause, with Girton College opening in 1869 before taking up its permanent position in Cambridge in 1873. If it were not for these ladies, I would have never qualified as a solicitor (US translation: lawyer).

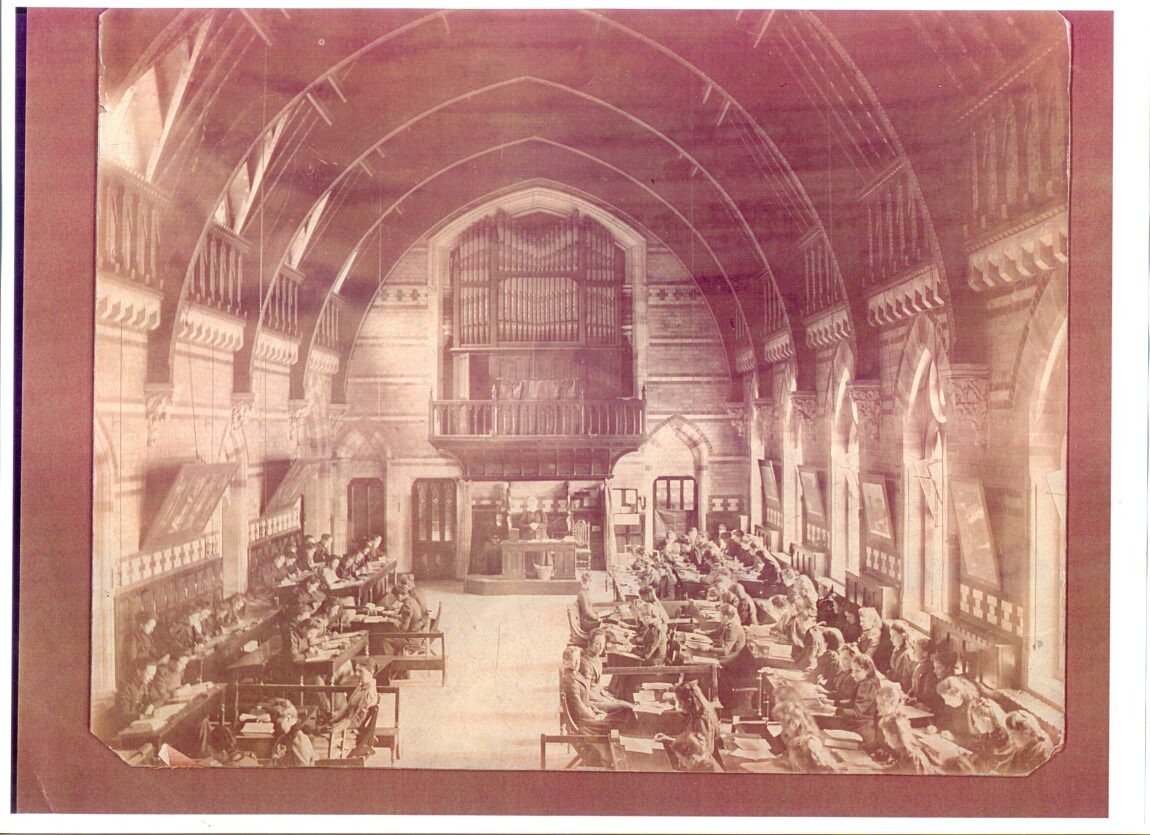

The architecture of Cheltenham Ladies’ College was and still is impressive. The photo at the top of this piece shows the Lower Hall in the late nineteenth century. By the time I attended, a mid-ceiling had been installed, dividing the great open space into two, with a grand staircase connecting the floors. Light still filters in from the stained-glass windows, illuminating classrooms and the library – as seen in this 1980s photo of a classroom above the Lower Hall. I attended a little before this, but this type of classroom is familiar to me.

In my home town of Huddersfield, the Union Discussion Society considered the question of education for women. In 1884, the motion that women should be granted all the political and educational advantages enjoyed by men was defeated, as was the 1886 motion that the social position of women, confined as they were to the home and with no right to vote, was anomalous and degrading.

By 1954, women were finding their way into finance, banking and the law. The all-male cohorts took seriously the motion put before them, that the deterioration of home life was resulting in serious consequences. In protest at the prospect of a lack of tea on the table when they got in from work and dust on the skirting boards, the motion carried.

When I began my legal career in Huddersfield in 1985 as a newly qualified solicitor, some of the old guard doubted that women could match their expertise. Over drinks in the local pub, where many of the town’s professionals gathered on Fridays, several complex contract law questions were put to me by an all-male audience. I held my own, and they supped quietly as they mused upon the march of women into their professions and partnerships.

Peacock on the Moon is unique in telling, amongst other things, how my mother never took her own education as seriously as she did mine. I can say she never understood the modern working environment, but she was determined I should not be buried alive under a pile of ironing without recourse to money of my own. As it turned out, I ended up buried under a pile of legal documents instead.