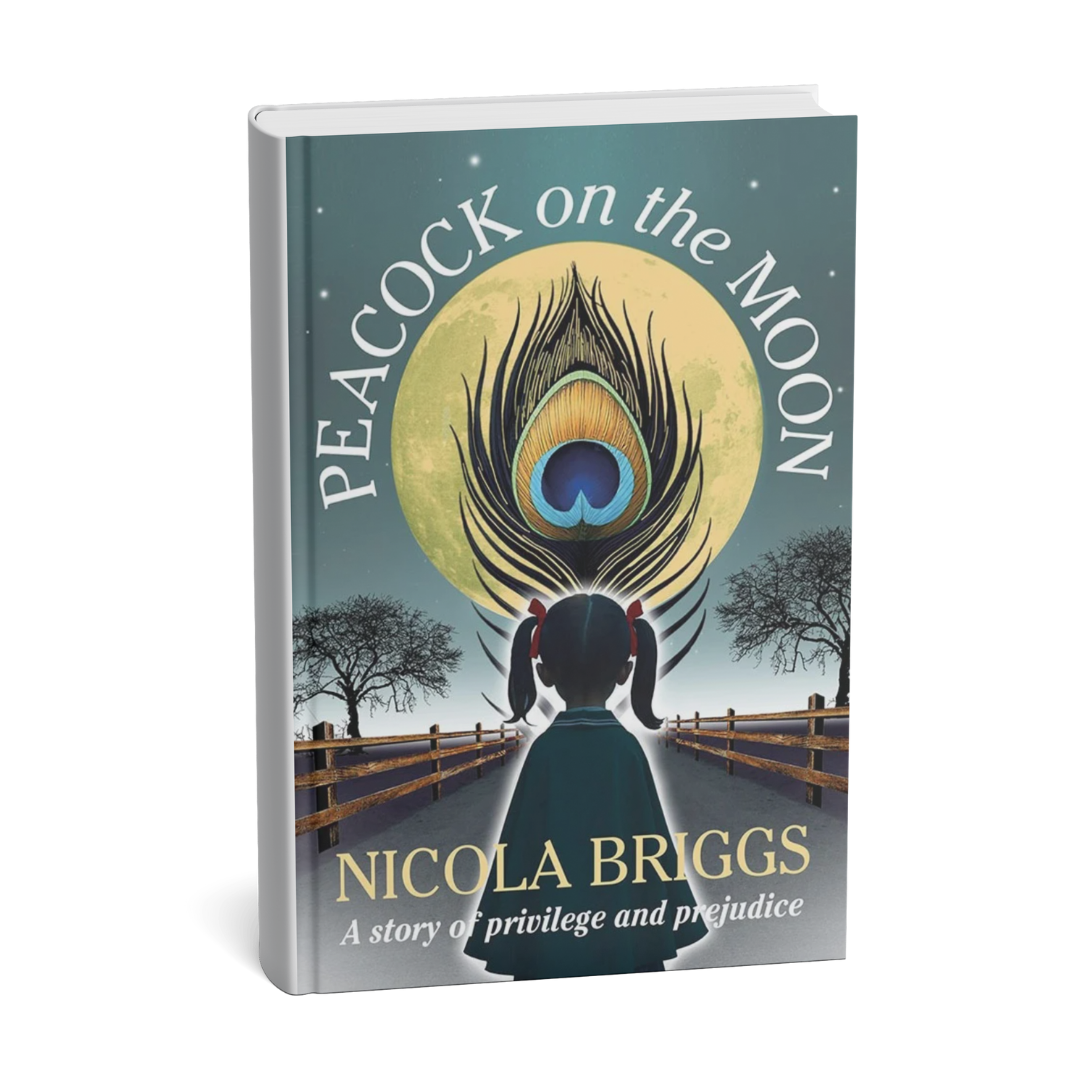

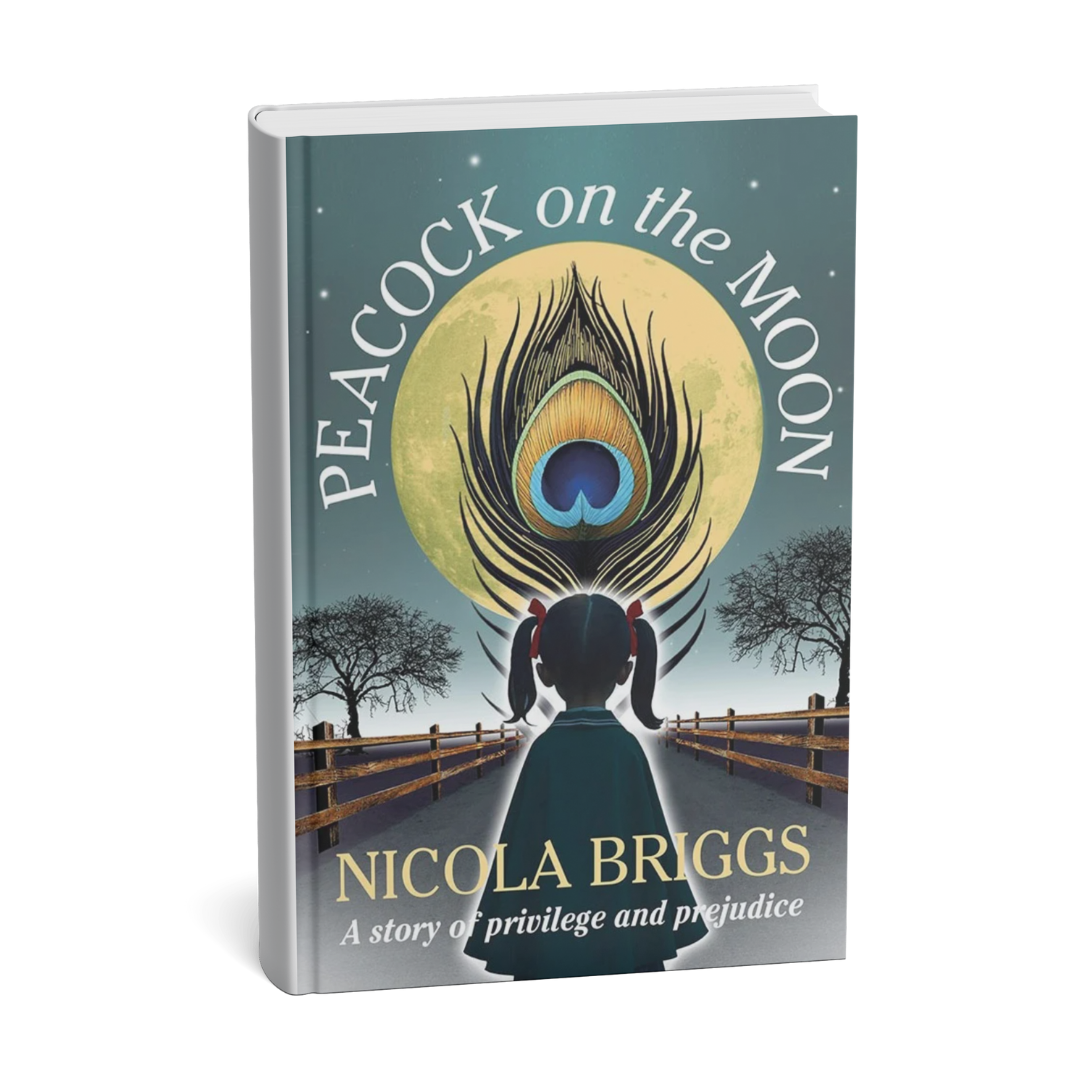

Peacock on The Moon

Our story starts with a young girl who is sent to an English boarding school in the 1970s, but we find ourselves drawn into the views within her family that are to become part of her makeup. That girl is me. We don’t really look at our parents until we have made it to our own middle age, with some of what we unearth coming as a surprise, or as confirmation of that which we already suspected. These discoveries only lead to further questions, but death or dementia can remove the opportunity to go straight to the horse’s mouth, and, more than likely, the truth would have been buried anyway in answers distorted by a desire to present a more perfect self.

You may claim an awareness that the ‘60s and ‘70s are decades known for the rise of anti-immigration sentiment, but do you know how Middle Englanders came to believe they had the right to behave so? I grew up in a family where the head of the household led our behaviour, until we came to develop minds of our own, and, once we had minds of our own he hated us for it. Aligning his rhetoric to that which is in favour today reduces its impact. I have chosen to provide you with the facts as to how it was, our facts, a snapshot of non p-c social history from a time that is now half a century ago.

My privileged childhood is one you may feel lucky to have escaped, but then I cannot speak for what is your normal. This story is about mine.

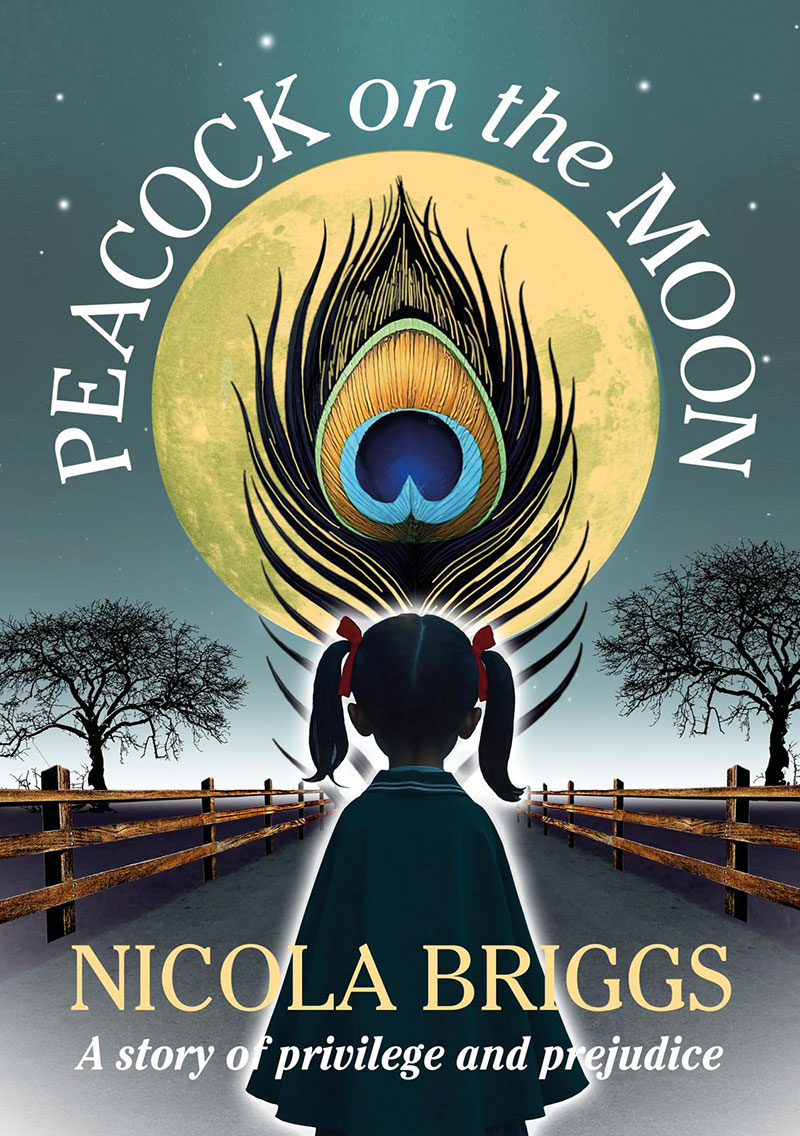

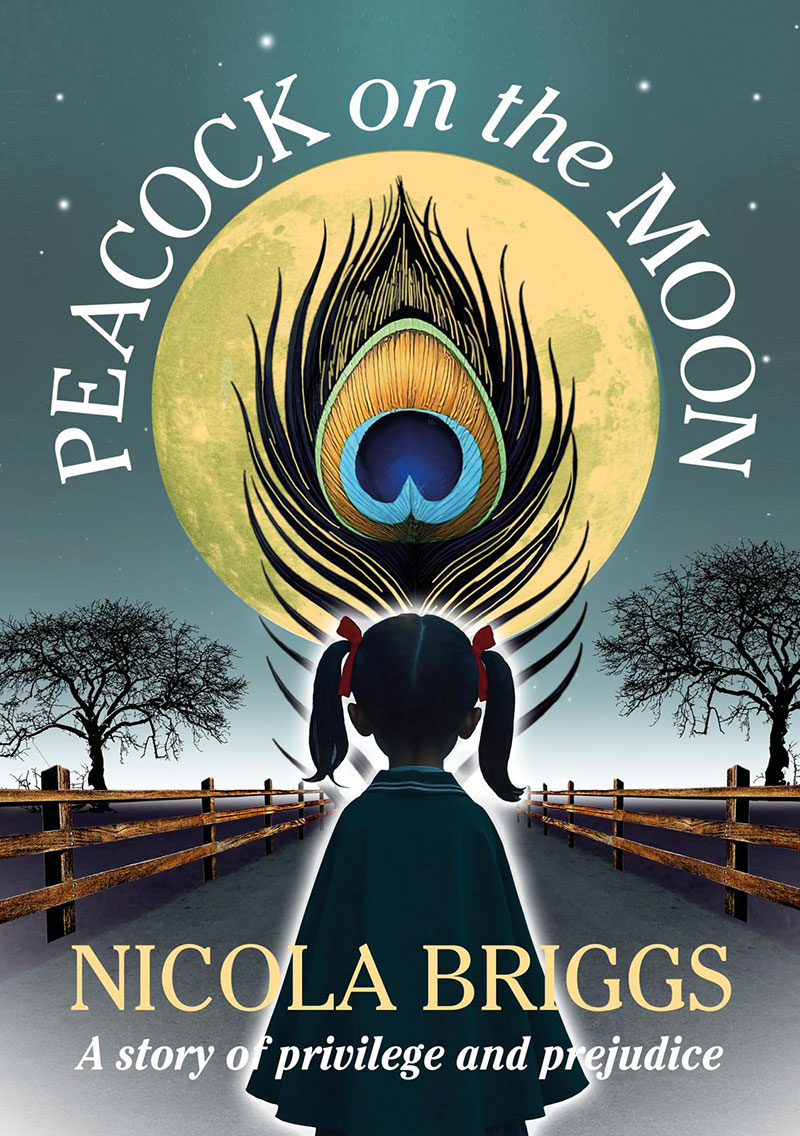

Peacock on The Moon

Our story starts with a young girl who is sent to an English boarding school in the 1970s, but we find ourselves drawn into the views within her family that are to become part of her makeup. That girl is me. We don’t really look at our parents until we have made it to our own middle age, with some of what we unearth coming as a surprise, or as confirmation of that which we already suspected. These discoveries only lead to further questions, but death or dementia can remove the opportunity to go straight to the horse’s mouth, and, more than likely, the truth would have been buried anyway in answers distorted by a desire to present a more perfect self.

You may claim an awareness that the ‘60s and ‘70s are decades known for the rise of anti-immigration sentiment, but do you know how Middle Englanders came to believe they had the right to behave so? I grew up in a family where the head of the household led our behaviour, until we came to develop minds of our own, and, once we had minds of our own he hated us for it. Aligning his rhetoric to that which is in favour today reduces its impact. I have chosen to provide you with the facts as to how it was, our facts, a snapshot of non p-c social history from a time that is now half a century ago.

My privileged childhood is one you may feel lucky to have escaped, but then I cannot speak for what is your normal. This story is about mine.

Excerpt from Peacock on The Moon

In this chapter I am returning home after my first full term at boarding school

The trouble with depositing your children around the country is that they have to be picked up and, what with there being so many exeats, holidays, and half terms, weekend entertainment for grown-ups is at risk of being severely curtailed unless every effort is made to combine the two. It is useful to know a similarly fragmented family as the burden of heavy mileage can then be shared. I record this long-awaited day in my diary: ‘END OF TERM. Mr Elliott brings me home – kissed cats – tydied up bedroom from unpacking for it was a mess in my opinion – stayed up late – Helped Mummy with cocktail party – they go out – read comics – glad to be home.’

My first thought is to stick my nose into Basil’s neck to inhale his dogginess, my second to strangle him with hugs, my third to release him, as orders have been issued that it is time to equip the best room, or drawing room as it is now signposted after our visit to some prestigious house in the Cotswolds, with the ashtrays and coasters that will protect our antiquated mishmash of dark mahogany, walnut, and yew. Carved ivory crocodiles, restored Staffordshire sheep, a chipped Meison bull, peer from the other side of the heavy glass-fronted Victorian display cabinet, fresh from their outing, yellow bits of duster fluff deposited in their crevices. Mrs Moorhouse has prepared the house for guests, and as soon as I have offloaded my school uniform into the laundry basket I set about the important job of exhibiting crystal flutes and skewered sausages on silver platters. Mother and Father are excited about their pre-dance booze-up. I am excited to be home for Christmas, to receive a greater parental allowance than was on offer at half term. I want to return to the life I had before. I don’t like my new one.

We watch from the staircase in pyjamas, foreheads resting against the cold balustrade, theatre goers without tickets to this pantomime. Cars roll up one by one to drop stockinged legs in high heels at the front door before they glide down the length of the drive and park up. Glass clinks against champagne bottle, the laughter grows, voices vie to be heard over the general mumble, the reek of cigarettes bleeds into the curtains.

Adult parties seem to demonstrate everything Father calls out as unseemly behaviour for gentlefolk: flirtatious eyeballs resting on another man’s property, raucous encouragement from wives delighted to show their disinterested husbands they are not without beguiling charm. Lashings of perfume and aftershave drip off intrigue, undercurrents, lust, revenge on a plate. In this game of charades, the actors have to guess who is double-crossing whom, the double agents amongst them hoping they can seek out the predilections of others whilst hiding their own. And then everyone is gone, but not the ash-filled carpets, discarded butt-ends, lipstick-stained glass rims. Peace descends. I have returned. They have gone out. After a bout of television, the babysitter retires us to bed, me with a cat under each arm. The fluffboxes seem pleased to see me.

For all the frivolity, Father’s diaries are painting another picture. A tension is mounting as he notes the interest Mother is receiving from other men. They are caught up in their own dramas so I’m not sure they have detected the change in me. A quietness has descended. The supermarket trip is now all about being by my mummy’s side, holding onto the trolley, taking in her scent and her voice. She tells me to stop clinging and choose something I want, but it isn’t on any shelf and won’t be found stuck up with a price tag. Unable to tell her this, smarting at being pushed away, I pick up a pack of biscuits. She is used to having one child, so three seems like a crowd. In the morning, revelling in the ownership of a bed that has no time limit on its occupancy, I hear her laying the breakfast table, lining up cereal packets for us to choose between Ricicles, Frosted Flakes, and Sugar Puffs. What had been normal before is now exceptional. There is no clanging bell to summon me, just the gentle radio in the kitchen playing Kenny Rogers or the Bee Gees or the Carpenters; Mother has swapped love for love songs.

My dolls and teddies have been waiting for me (although Angela has obviously had her fingers all over them), Basil is still happy for me to lie on top of him in front of the coal fire, and life seems almost normal. Apart from the sickness that starts on day one; the jelly wobble malaise of knowing I am here, but soon not. Whereas everything was just there, always there, now it exists for the sole purpose of teasing me as to how life might be if I were to attend a local school. Four weeks at home sounds good, but the holiday has a predetermined end which every day will drag closer. Time has a purchase price which I would be only too happy to pay, both to have more and to have less, relative to the beginning or end of term. My Christmas list to Father Christmas should have started with a request for a Groundhog Day, preferably about 22 December, when the excitement of prospective presents is still electric, and the end of the holidays is sufficiently distant to be of no immediate threat. That happy day could start and end in a loop, as a way of avoiding those long days spent hoping things might be different, even when this was a known impossibility.

Would they believe me if I spilled the beans about my isolation at school, about having no friends, about my fear of their next prank, or would that be like talking to the jailor, with any indirect complaint to the housemistress only inviting further torment from my fellow dormitarians?

The grandfather clock guarding the bottom of the stairs sets the rhythm of the house from its sentry box, plodding out its tick and its tock as it shunts the days along in its sleep; it is in no rush and has nowhere to go. Time is on its side. Time is forever. Standing beneath its busy face, all fussy dials and Roman numerals, I know it to be a liar. YOU, you eyeless stately timepiece, are a LIAR. You are as useless to me as our stump of a sundial on a cloudy day from its raised seat amongst the roses. Your poor relation, the wristwatch that follows me everywhere, tells me the truth. It tells me I have only an hour left at home, or an hour to wait before Parents arrive to see me, or an hour before I might get a letter from Mother. Time is everything. I am eleven and precocious in this knowledge.

They are in and out to dinner parties, with plenty of luncheon gatherings to which they can take us. Mother worries about what to wear and whether Father will finish what he is doing in time. Father worries whether he has enough booze in the cellars for when it is their turn. Bring a bottle parties are poor form. The host provides. You would not want to seem to be suggesting the host lacked a wine cellar, or that you believed his knowledge or wallet to be deficient. We are getting dressed up and in and out of the car on a daily basis and, once there, when the champagne is poured and the cigarettes are lit, the babble turns into a din, with us being collared by Father from time to time. “Nicola is having a great time at school. She has started at Cheltenham Ladies’ College, you know. That’s right, isn’t it, Nicola.” As I write, I mull over whether I should add a question mark but have decided it is not a question. It is a demand.

I nod in reply as I eye up the chocolate meringue castle Mother has brought as her contribution. She is known for her prowess with puddings and this is no exception, all the more so because it has not slipped off the lid from underneath the inverted cake tin to decorate the car on the journey over. The slightly undercooked meringues, toffee-ish and soft, are stuck together with chocolate buttercream to form a pyramid of beckoning joy, which only a bowl of cream can perfect. An emergency carton of buttercream sticks to her lipstick in her handbag, ready for that improvised re-construction should Father be a bit heavy on the brakes or take a corner too fast.

With lunch served, I am in, purposeful, secretive, it being a certainty there will be nothing to take home. Adults lean over tables to collect their poached salmon or game terrine without noticing the spoon burying into the shimmering extinct white volcano, streaked with lava flows of cold brown butter. I cannot eat another thing between getting home and the babysitter arriving as I am feeling a little sick. I was right, there were no leftovers. Somebody ate it all.

The honour of decorating the Christmas tree falls to me this year and, keen to get going, I am in and out of the attic and up and down the stairs with greater enthusiasm than was ever applied to the lacrosse field. All seems in order. Our crowning golden angel has not been de-robed by mice. The wings of my beloved white goose are still intact for yet another season of flapping up and down on its spring, attacking those of a certain height who venture too close to the central light fitting in the inner hall. I regret passionately my not having the patience last year to restring those baubles where the threads had broken. The tedious task of making up loops with which to append them to the tree is fiddly, clumsy fingers crushing the funnels on the more fragile glass soldiers and cars, making the act of having carefully stored them away fairly pointless. There is plenty of suitable cotton thread round and about, what with the colour of my school uniform being sort of fir green. I know what to do here, at home, when there is no whispering behind my back, nobody vying to replace me in this activity. It is my role, as of right, to be their daughter and eldest child, a role I fill with ease. My discomfort is in not knowing what that role entails when I am away, out of sight.

Express an Interest

For book news and a release date, please complete the form below. Nicola will email you with news, ways to purchase her memoir, and how to get an exclusive signed copy.

You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the email.

Express an Interest

For book news and a release date, please complete the form below. Nicola will email you with news, ways to purchase her memoir, and how to get an exclusive signed copy.

You may unsubscribe at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the email.